While researching Horrockses Fashions a few years ago I bought a couple of their housecoats. These full-length glamorous garments seemed so far removed from the more mundane dressing gown that it lead me to wonder what kind of women would have worn them, in what circumstances and why had they disappeared from women’s wardrobes? My fascination led to a conference paper on the subject and during lockdown I finally found time to go back to my research and decided to share my musings. What we wear at home has taken on a new significance recently, maybe you chose to stay in your pyjamas all day or conducted a Zoom meeting in your dressing gown? Maybe this is the right time to rethink what we wear at home and revive the housecoat? Hopefully this rather lengthy piece – will provide food for thought.

INTRODUCTION

Horrockses Fashions, 1947 (Author’s Collection)

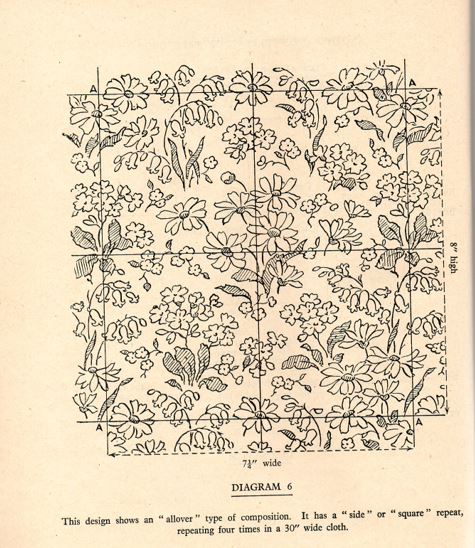

In the 1940s and the 1950s the housecoat (sometimes known as a house gown or hostess gown) was a popular component of a middle/upper-class woman’s wardrobe; it was an elegant, tailored, full length and often voluminous indoor outfit that has no equivalent today[1] . Its meaning and purpose were contested and there was disagreement about what it was for and when it should be worn: was it a more glamorous cousin of the dressing gown; was it suitable for wearing to dinner parties; was it practical for household duties; could one answer the front door wearing one? Its popularity was short-lived and although the term continued to be used for a range of less formal garments worn before going to bed and after getting up, by about 1960 the version discussed in this paper had in effect disappeared.

This paper seeks to understand this very particular category of garment and the contexts for its emergence, development and disappearance. It examines the life cycle of the housecoat, focusing on its lineage, its conception in the 1930s and its demise at the end of the 1950s. It explores attempts by some in the clothing trade to market what it hailed as a ‘new’ product for a new modern age and uncovers the reasons for the difficulties it had in explaining the product to potential consumers.

At the heart of the study is an examination of the trade magazine, with a particular focus on the journal Corsetry and Underwear.[2] Trade journals such as this provide valuable insights into the attitudes and preoccupations of manufacturers, wholesalers and retailers. Such publications up-dated their subscribers on technological advances, relevant political and economic developments, the latest news on fashions, fabrics and trimmings, as well as providing information on the purchasing habits of consumers, ideas about selling and developments in markets at home and overseas.[3] In the case of the housecoat they offer evidence about the development of this ‘new’ garment, the trade’s understanding of it and the strategies used to persuade women to purchase them.

What emerges from this study is a contradictory item of clothing. The housecoat was situated on the threshold of the bedroom and the rest of the house, it was neither outdoor wear nor lingerie, and could even be worn to host informal dinners at home. It also seemed to be simultaneously glamorous and domestic. These oppositions led to confused explanations of the housecoat’s function which were reflected in the advice provided to manufacturers and retailers in the trade journal. The struggle to fix its meaning and function in the middle years of the twentieth century was paralleled by a period of instability and change for women, when new discourses were seeking to reinforce the association of domesticity and femininity, the housecoat can be read as emblematic of that discourse.

A REINVENTION OF THE TEA-GOWN?

The confusion around the function and naming of the ‘housecoat’ begins long before its birth and has its genesis in the development of a variety of dishabille clothing in the nineteenth century. There were numerous variations in this category of garment and they ranged from ‘dressing gowns’, ‘tea gowns’, ‘robes d’interior’, ‘peignoirs’, ‘negligees’ and ‘rest gowns’. Such complexity reflected the fact that women from upper-class fashionable society changed their clothes many times during the day, with specific garments for particular activities. The practice was also driven by manufacturers and retailers as it encouraged consumption. A 1908 catalogue from the Parisian department store La Samaritaine illustrates some of the range of dishabille clothing available.

La Samaritaine, 1908

An upper-class woman’s ability to navigate successfully the rules of what to wear and when, was a demonstration of her sartorial expertise, and consequently her social standing. The fashion designer Barbara Hulanicki, writing about her aunt Sophie’s in the late 1940s and early 1950s, recalled her frequent changes of clothes during a typical day, this included a flowing pink satin peignoir in the mornings when she applied her make-up and ‘by the evening the tea gown made its appearance … a long garment made of silk velvet, crepe or brocade, somewhere between an evening dress and a dressing gown.’[4] The glamour of both these garments was a contrast to the more commonly worn dressing gown which was not considered to be suitable to wear in front of visitors, probably due to its loose fit and tie around sash that could easily fall open. The dressing gown was worn by men and women and had developed from a male banyan or nightgown in the nineteenth century.[5] They were usually worn over bedclothes when getting up, going to bed, or preparing for a bath. There were connotations of slovenliness if worn during the day, which was highlighted in the 1957 British film ‘Woman in a Dressing Gown’ in which the main character, a housewife played by Yvonne Mitchell, lived in the garment which is used to signify her depression, loss of interest in the world, and general sloppiness.[6]

The direct ancestor of the housecoat is the tea gown rather than the dressing gown. The tea gown was an indoor dress developed in the 1870s, when women’s clothing was tight-fitting and constrictive. It allowed upper-class women to temporarily abandon their fashionable bustles and corsets for a short period from the late afternoon to the early evening before dressing for dinner. Initially the tea gown opened down the front and could be put on without the assistance of the ladies’ maid. Favoured materials were silk, satin, chiffon and lace and tea gowns were often decoratively flounced and trimmed and had elaborate sleeves and collars. They gradually became more fitted, following the fashionable silhouette and were included in the ranges of the most fashionable designers and couturiers. By the 1890s the tea gown had progressed from attire suitable for wearing at tea, to a garment appropriate for informal dining.

Even though corsetry became less restrictive, the tea gown continued to be a popular component of an upper-class woman’s wardrobe into the 1920s and 30s. The American etiquette expert Emily Post, writing in 1922, described the garment as ‘a hybrid between a wrapper and a ball dress. It has always a train and usually long flowing sleeves, is made of rather gorgeous materials and goes on easily, and its chief use is not for wear at the tea-table so much as for dinner alone with one’s family’.[7] Whilst Good Housekeeping advised its readers in 1936, that ‘No trousseau can be complete without a tea gown of the type which is suitable for informal entertaining and dining à deux at home.’[8]

Good Housekeeping, May 1936, p.63

The garment was not exactly lingerie, but nor was it suitable for wearing outside the house. Examples illustrated in fashion magazines, such as Vogue in the twenties and thirties, were usually placed in glamorous settings: a reception room with a large chandelier, at the bottom of a sweeping staircase, but not usually in the bedroom. By 1930 Draper’s Record suggests it was becoming old fashioned, noting that is was now restricted to ‘the more conservative section of the feminine public’.[9]

Housecoats by Hélène Yrande (left) and Elsa Schiaparelli (right) [Vogue, Oct 18 1933, p.87]

As manufacturers attempted to distance the product from its precursor, there were numerous efforts to re-name the garment. This is highlighted in Drapers’ Record in August 1937 with the illustration of a hybrid garment by Horace Corke & Co identified as a ‘house-coat-cum-dressing-gown’.[11] It is described as made from ‘Zenana’ cloth from Courtaulds and has a close fitting bodice, with buttons arranged off-centre that extended from collar to waist. The ankle-length skirt has an off-centre opening, the sleeves are long with buttoned cuffs. However, the tailoring in this example is very different from the loose-fitting wrap around style normally associated with dressing gowns. By the early 1950s when ‘housecoats’ are well established, the term ‘tea-gown’ still appears very occasionally when it was used to describe ‘a rather exclusive part of housecoat ranges’.[12]

Horace Corke housecoat. Drapers’ Record, 28 August 1937

‘THE HOUSE-COAT IS HERE’

After its first appearance in Vogue in 1933 the housecoat appeared only occasionally throughout the 1930s and it was not until the end of the decade that it could be seen regularly in the trade press. A feature in Drapers’ Record from October 1937, declared ‘The house-coat is here’.[13] It highlighted the fact that they were designed ‘with an eye on fashion’ and had advantages over the loose-fitting dressing gown as ‘they fasten more firmly, and are more comfortable to lounge in. They are naturally more flattering to the figure; are easier to display, and therefore easier to sell’.[14]

Drapers’ Record, 23 October 1937. p.50

The journal encouraged its retail subscribers to differentiate the housecoat from other similar garments, in 1940 it contrasted the dressing gown – with ‘its straight mannish lines’, with the housecoat, with its ‘fitted top and flaring skirt’. The term housecoat makes its first appearance in Corsetry and Underwear Journal in June 1939 with an illustration of an example by Howard’s Lingerie. This floor-length model has front-fastening buttons extending to the knee, the bodice fits tightly and has a large falling collar, the short puffed sleeves emphasise the shoulders and echo the fashionable silhouette.[15] All of the early housecoats resemble full-length coats rather than dressing gowns.

The introduction of the housecoat (or house gown) into the product range of the manufacturer Chilprufe in the early 1940s provides an illustration of how one company launched and promoted this ‘new’ garment. The Leicester-based firm was founded by John Bolton who established the Chillproof Manufacturing Company in 1906 producing woollen underclothes for children and by 1930 had added ladies’ embroidered dressing gowns to its product range. The firm became Chilprufe Limited in 1936, by which time it had diversified further, making children’s tailored coats and nightclothes as well as women’s nightdresses, slippers and vests, and later swimwear and men’s underwear. Chilprufe specialised in pure new wool clothing and emphasised practicality, warmth and comfort in its marketing literature. In 1938 the term ‘house gown’ first featured in its sales brochures[16], pictured alongside dressing gowns but distinguished from them by their button fastening, tailored bodices, collars with revers and longer lengths.

In sales catalogues, dressing gowns are always 52 inches long, whilst house gowns are 54 inches and often trailed on the floor, suggesting more limited practicality. The tailoring involved meant they were more expensive than dressing gowns. The wholesale price of the latter was between 33 to 66 shillings, while a Chilprufe house gown sold from 51 to 72 shillings. By the early 1940s the word ‘gown’ had been replaced in Chilprufe’s literature by ‘coat’, probably to distance the product the class-ridden and now old-fashioned ‘tea-gown’.

In 1945 Corsetry and Underwear explained that the popularity of the housecoat arose directly out of war-time conditions, noting that an elegant version was able to function as a ‘fitting substitute for war-banished evening gowns’.[17]

An advertisement appearing in its pages in 1941 described the housecoat as an ‘an indispensable item in the wartime wardrobe’.[18] Fuel shortages meant it was essential to wrap up warm at home and the housecoat is recommended as a way of achieving this. [19] Examples made of wool were particularly appropriate. The illustrator Pearl Binder wore wool versions during the war and after, which were made for her by a dressmaker. [20] Air force personnel were billeted with her and her family during the war and her illustration of their arrival clearly implies the acceptability of receiving these temporary guests wearing a housecoat. With clothes rationing a fact of life for several years after the war the benefits of the housecoat as a way of saving on one’s clothes was also highlighted by Good Housekeeping. [21] At the beginning of the war many manufacturers were left with large stocks of evening dresses which they were unable to sell and several converted them into housecoats by adapting them and giving then front fastenings. [22] Such adaptations probably aided the popularity of the housecoat in the 1940s. However, some of the confusions encountered later probably have their origins in this war-time culture of, re-use and multi-function.

DEFINING THE HOUSECOAT

By the mid-1940s the term ‘housecoat’ was firmly established in the sartorial vocabulary of the British consumer. As the garment was not entirely new, many consumers, particularly the wealthy leisured class, would have understood it as ‘the newest version of the tea gown’, and would have a tacit awareness of when and where it was appropriate to wear one. But manufacturers were trying to reach a much broader customer base than this relatively small number of women. It was particularly crucial, therefore, that retailers found ways of selling the housecoat to women who had no experience of them. In order to stimulate consumption manufacturers had to persuade women that it was indeed something that they had to have. In its efforts to do this it was important that they explained clearly what the garment was for and when and where it could be worn. This was done initially through messages conveyed in advertising and then later with the help of the trade press through numerous feature articles, including ideas on selling for retailers. For example, a 1953 piece suggested that retailers should ‘approach the fashion writer of your local paper, show her your stock and arouse her enthusiasm … get manufacturers to co-operate with their own advertising. Tie up the promotion with the store’s autumn fashion show’.[23]

As the 1940s progressed the attention given to the housecoat increases. At this time the efforts of manufacturers and the trade press to explain the garment were limited to notions of elegance and practicality, with a general consensus regarding the function of the garment as an item of indoor dress that could be worn for dinners at home with close family and friends, it was recommended as ‘the ideal garment for informal social evenings at home’,[24] or for ‘quiet relaxation’.[25]

There were a variety of companies producing housecoats during the 1940s and 1950s, some were established manufacturers of lingerie including nightdresses and underwear, others specialised in dressing gowns and housecoats, while some diverged into housecoat manufacture via fashionable outerwear. Howard’s (Lingerie) Limited was an example of the first type. It was the first manufacturer to advertise its housecoats regularly in the Corsetry and Underwear.

The firm, established in 1936, explained that its housecoats were ‘warm and comfortable, and can be classified as “good dressing” for informal occasions’.[26]

The elegance of its product was emphasised in its advertising in the trade press. An example from 1946, illustrated a floral printed satin housecoat with long balloon sleeves ending in a deep buttoned cuff, the bodice fits tightly around the waist and bust and the shoulders are padded and follow contemporary fashion.[27] The addition of elaborately dressed hair, ear rings and elegant sandals, with the model resting her hand on a stylish armchair gives the ensemble the impression of sophistication and supports the trade’s message that the housecoat was suitable for evening wear at home.

Corsetry & Underwear, July 1946

Specialist housecoat manufacturers included Lydia Moss and Kay Sidney Limited. Kay Sidney‘s output was dominated by styles with full length front closing zips and elasticated waists, designs accentuated practicality and descriptions in advertising noted warmth and comfort.

A number of companies whose chief line was women’s fashion also produced housecoat collections. One such firm was Horrockses Fashions, a London-based subsidiary of the cotton manufacturer Horrockses Crewdson & Co Ltd, established in 1946 as a way of promoting the parent company’s cotton cloth. Horrockses Fashions included housecoats in its ranges from the outset. This was partly a response to the rising popularity of the garment. But as a manufacturer of fashion lines, and particularly seasonal cotton summer dresses, the company needed to make sure its making-up factories were producing all year round, housecoat manufacture satisfied this requirement. Management minutes indicate that the housecoat operation was also useful for using up surplus cloth not needed for the production of dresses, either as the main fabric or as linings. In the late 1940s and early 1950s housecoats made up between ten and fourteen percent of their total production and was acknowledged a significant product in their range of merchandise.[28]

MODESTY AND RESPECTABILITY

The ideas of elegance and practicality that had dominated discourses around the housecoat in the 1940s continued to be communicated into the 1950s. But in their efforts to help manufacturers and retailers reach new consumers, the trade magazine also added an array of confusing and sometimes, contradictory messages around ideas of modesty and respectability, domesticity and glamour, and work and leisure. Explaining to potential consumers the appropriate occasions and locations for wearing the housecoat is something often referred to: was it dress or undress, to be worn upstairs or downstairs, could it really be worn in front of guests or to answer the front door? Corsetry and Underwear explained that a housecoat was ‘usually worn direct over underwear’,[29] this is confirmed by women who wore them at the time and implies that it was more like outerwear than lingerie. Concerns over how to categorise the garment were evident when versions of the housecoat first appeared. When Chilprufe launched its house gowns in 1938 they were described as ‘An innovation! An entirely new conception of house wear…ideal for every indoor occasion, for breakfast to informal dining! Gowns eminently smart and practical, with no suggestion of des-habille!’[30] Chilprufe’s attempt to fix its function as all-purpose ‘house wear’ and reject completely any association with lingerie illustrates the importance of explaining a ‘new’ garment to customers.

Page called ‘Presents of Chilprufe’ from a Chilprufe catalogue n.d (University of Nottingham Manuscripts and Special Collections -BCH 3.10.4.4)

In the housecoat’s early history there was a level of anxiety and confusion felt by retailers about its function and consequently how to place and promote it in their stores. This is borne out in an incident recounted by the Nottingham manufacturer of tailored leisure wear, Cyril Myers who explained to the Corsetry and Underwear Journal his initial difficulties in selling his housecoats to some retailers.

He recounted an incident from 1941 when one Scottish customer was horrified when shown a photograph of a Myers’ housecoat, commenting: ‘If my wife came down in the evening wearing such a garment, I’d send her back to dress properly!’. [31] His comment illustrates a middle-class concern about respectability, decency and modesty that was not so evident among the wealthy leisured upper- class in relation to the tea-gown. But as housecoats were being targeted at the masses such concerns had to be addressed. By 1945 it would seem that retailers were becoming clearer about the function of the housecoat as a smart, semi-formal indoor dress, and the Scottish retailer’s initial horror receded and he placed a large order with Myers. The same year Myers was able to move to a new factory in Nottingham and treble its production of leisure-wear, including housecoats.

The early 1950s sees a peak in editorial coverage of housecoats in Corsetry and Underwear. In a 1953 piece ‘Taking Shape: housecoats hit the headlines’, the journal felt the garment was so well established it warranted a review of its history- from ‘a drab duty number’ in 1937, to, in 1953, ‘a garment of grace, style and in many cases beauty of which forms an effectual mask for its essentially functional purpose’.[32] The journal continued to feel the need to reassure women via, retail sales staff, about questions of when it was appropriate to wear the garment, noting that a woman wearing one could, ‘With no embarrassment whatever about whether or not she has that “just right” look [she] may gaily open the door to the milkman, the doctor or the personal friend’.[33]

HOUSEWORK AND LEISURE

In seeking to reach a wider market conflicting messages were given suggesting that the housecoat was suitable attire for both domestic chores and for wearing in one’s leisure hours. Such contradictions reflect the fact that women’s roles were facing re-evaluation. During the Second World War large numbers of women had experienced work outside the home for the first time. But the immediate post-war years saw much discussion of their key place in the re-establishment of domestic harmony. There was a renewed focus on the home, particularly in terms of it as a privatised family space.[34] The home increasingly became a site for leisure activity and consumption and at its centre was the housewife, whose role at the time was being redefined and explained in women’s magazines and self-help manuals. For the middle-class woman this new emphasis on the home coincided with the virtual disappearance of the domestic servant, and the growing prominence in her life of domestic housework. This corresponded with an expansion in the number of women in paid employment who had to fit housework around their jobs. Such factors are reflected in the kinds of messages constructed in order to sell the housecoat.

During the 1940s there was only an occasional acknowledgement in the trade press of women’s changing roles. This is represented in an advertisement for one of Victor Jacobs’ housecoats in Corsetry and Underwear that described its product as suitable for ‘informal occasions when busy women take a well-earned leisure at home’.[35]

Corsetry & Underwear, Feb 1942, p.12

But by the early 1950s discourses around the housecoat are much more explicit and seem to require the woman to be a leisured society hostess and an accomplished and organised housekeeper, cook and cleaner, and this dichotomy is expressed clearly in Corsetry and Underwear’s discussions of the housecoat. The established description of a housecoat provided by the trade press and manufacturers’ advertising – as a full-length, full-skirted voluminous garment with a tight-fitting bodice – might have been suited to the activities of a leisured hostess, but was highly incompatible for the domestic chores most women were faced with at the time. Particularly impractical were housecoats with long, flowing sleeves and skirts which trailed the floor and consisted of many yards of fabric.

These stylistic features were combined with frequent references to glamour and elegance which found there way into discussions of the housecoat in women’s magazines and mail order catalogues. Kay’s Spring/Summer catalogue of 1956 titled its housecoat page as ‘At Home Glamour, Luxury Housecoats to fulfil your every dream’.

Kay’s Catalogue, 1956, p.49

However, such discourses were sometimes at odds with the realities of life for many. One woman recalled owning several housecoats before marrying. She wore them when staying in hotels and having breakfast in her suite and in the evenings at home. When her parents went out for dinner and brought back visitors, she would meet them in her housecoat. She stopped wearing them once she was ‘married, had children, ran a household, washed nappies, cleaned fires out, came down to earth’.[36] Although Corsetry and Underwear claimed that some versions of the housecoats were suitable for women who ‘look after the home, collect the coal, wash up the breakfast dishes and light fires’[37] the only kind of housework illustrated tended to be the less strenuous side of homemaking – flower arranging, and serving coffee or cocktails.

There were adaptations to the housecoat to facilitate housework such as examples that allow the sleeves to push up and ‘avoid knocking over cups and saucers’[38] and the introduction of three-quarter sleeves.

Discourses around leisure were frequent and Corsetry and Underwear titled a 1955 article – ‘For Luxury Lounging’.[39] However, the content of the piece concentrates on the housecoat’s general versatility. Women’s magazines and newspapers recommend its suitability as a garment for watching television. An advertisement for Harrods in Vogue in 1951 described the featured housecoats as ‘Here’s leisured elegance in cosy casuals – designed for television or fireside stay-at-home evenings’. [40]

Gwen Robyns writing in the Evening News in 1952 impressed upon her readers the importance of looking elegant during one’s leisure hours. Her feature ‘Are you a tatty viewer?’ recommended a fitted, elegant housecoat for television watching.[41] The association of the housecoat with leisure is also emphasised in the description of some manufacturers as producers of ‘tailored leisurewear’.

EMPHASIS ON BEAUTY AND FEMININITY

The styling of the housecoat paralleled Dior’s fashionable ‘New Look’ introduced in 1947. Housecoats tended to follow the New Look silhouette, with nipped in waists, voluminous skirts and sloping shoulders. In the fashion illustrations and advertising images that were frequently seen in Corsetry and Underwear, the artists tended to exaggerate the size of skirts, the smallness of waists and the general romantic and feminine qualities of the garments. The exaggerated sexuality and glamour that they suggested was perhaps at odds with the more domestic connotations seen in some commentaries.

Corsetry & Underwear, 1952

For all her roles, the woman was required to be ‘feminine’ which is highlighted in a 1955 article in Corsetry and Underwear titled ‘Cool elegance: housecoat and fabrics for summer promotion’.[42] The piece proposes various approaches to retail promotion, but foregrounds femininity as a feature to emphasise, ‘floor length (in most cases) and full skirted, the housecoat can afford a woman the expression of feminine graciousness’. The role of the housecoat as ‘an indispensable unit in a woman’s wardrobe’ is stressed and it is described both as ‘an easy-to-slip-into garment for early morning wear’ and ‘for informal entertaining at home’. [43] Femininity was also suggested by the dominance of floral fabrics. While some patterns were influenced by trends in fabrics for interiors, which meant that a woman in her housecoat could ‘strike a fresh and original note, and [which] blend well with modern furnishing schemes’. [44] A woman could quite literally become part of the furniture!

The key was to look elegant and attractive at every opportunity. In a 1953 piece titled ‘Fashion in the Home’, retailers were encouraged to ‘make “Beauty at Breakfast” your new selling theme’. Corsetry and Underwear suggested that they were much more aware of the realities of the lives of housewives than the popular women’s magazines, noting that they had been ‘urging married women to make themselves up before breakfast… a housecoat takes only two seconds to put on and with, say, a matching ribbon in the hair can transform the wearer from a sleep-sodden apparition into something that is really pleasing to the early morning male eye’. [45]

Corsetry and Underwear ran endless features on the design and functions of the housecoat and attempted to describe to retailers how they should display and sell it. An article from 1955 encouraged retail subscribers to promote the housecoat as a versatile item in a woman’s wardrobe:

‘When a woman enters a shop to purchase such a garment, she realises that she will want to wear it in the bedroom, in the kitchen, to lounge in it and to do the housework. As it is to be worn in the winter it must protect her against cold draughts when she collects the milk: because she must work in it, it must be strong enough to withstand household hazards, and finally it must be attractive enough to wear in the evenings.’ [46]

The impossibility of one garment being appropriate for such a range of activities is clear, but the mid-1950s saw increasing promotion emphasising the housecoat as an ‘all-purpose’ garment, whilst simultaneously encouraging retailers to persuade women to buy several housecoats in different styles suitable for different activities: ‘one for the practical purposes of a dressing gown and one in which to be glamorous.’ [47]

‘HOUSECOATS ARE HIGH FASHION’[48]

One of the aims of a journal such as Corsetry and Underwear was to advise its readers on the best way to reach potential consumers and in their efforts to help sales-staff they endeavoured to classify the housecoat. In June 1950 it identified ‘three housecoat style groups – the semi-formals, well-dressed looking casuals and the soft elastic types’.[49] These categories reflected the multiple activities that women encountered in the 1950s, and if sales staff were to be successful in communicating this effectively through displays and interactions with shoppers, the result would hopefully mean a customer might make multiple purchases. The ‘soft-elastic types’ described could be seen in the products from Kay Sidney, the casuals in Charles Lyons ‘Chaslyn’ range and semi- formals in the output of manufacturers such as Hitchcock Williams, a long-established London wholesaler, manufacturing ladies’ outerwear and the ‘San Paula’ range of housecoats which were characterised by smart tailoring:

Spafford-Jones of Newark Nottinghamshire and its competitor Cooper of Newark both specialised in the ‘semi-formals’ producing fashion-led garments for the middle and expensive market.

The discourse of fashion is repeatedly used, with Spring/Summer and Autumn/Winter ‘seasons’ referred to. Again the motivation is the desire to get women to buy more than one housecoat. Different weights of fabric are highlighted as being suitable for particular seasons. Corsetry and Underwear felt that the association of housecoats with the world of fashion was a ‘saving grace’ for the housecoat manufacturer and retailer, presumably as consumers might be inclined to replace their housecoat on a more regular basis. Features on housecoats focus on fashion and tailoring details, and they are usually distinguished from dressing gowns because of they were fashionably styled. This was particularly the case with the more formal housecoats or house gowns where such fashionable detail had been regarded as a key selling point throughout the fifties. Variations in general shape, sleeve and collar design are mentioned with one journalist referring to ‘important collars.’[50]

In 1959 Corsetry and Underwear reported that the design of housecoats was closely allied to couture and they particularly pick out the trapeze line for comment, claiming it was ‘…a gift to the housecoat designers, and now the up-to-date young woman can rest assured that she is contemporary…’[51]

Corsetry & Underwear, July 1959

The dominance of discussions of this kind also distances the housecoat from lingerie and connects them more closely to women’s outerwear, specifically coats and evening dresses. For fashion manufacturers that also produced housecoats, such as Horrockses Fashions, there was a synergy between the production of dresses and housecoats. Horrockses frequently borrowed bodice and sleeve styles for its housecoats from its evening and day dress designs. This relationship is also very much in evidence in sewing patterns available to the home dressmaker where the same pattern could be used for housecoat or dress.

Reproduction pattern (Etsy)

The benefit to the trade of the housecoat being sold as a fashion garment as opposed to lingerie meant that the consumer might be persuaded to purchase a new housecoat more frequently, and at least once a year. But some impatience is expressed with consumers. In 1953 Corsetry and Underwear noted that of the fourteen million potential buyers in Britain only one woman in fifty bought a new housecoat annually – ‘yet there was no reason why housecoats should not occupy as important a place in the average woman’s wardrobe as separates or her Sunday best’.[52]

‘ANYTHING GOES’[53]

The latter half of the 1950s saw formality in housecoat design gradually being substituted by more casual styles. The fitted bodice is replaced by the trapeze, A-line or empire-line styles. In 1957 Corsetry and Underwear declared that ‘The housecoat of today is an extremely comprehensive garment that covers most of the forms of attire which have been variously styled ‘bathrobes’, ‘negligees’, ‘peignoirs’, ‘wraps’ and ‘dressing gowns’ … in fact anything goes’.[54] The emphasis is resolutely on the practical with shorter three-quarter sleeves becoming more common and easy-care qualities emphasised. A shorter version of the housecoat by S.Travers first appeared in 1953 and another in 1955, but Corsetry and Underwear report a mixed reaction to them from retail buyers and they appear infrequently until the later fifties.[55] They are usually referred to as ‘shortie housecoats’ and sometimes as ‘brunchcoats’, betraying an American influence.

These versions were felt to be particularly appealing to teenagers and younger customers who were now wearing shorter nightdresses, suggesting they were more akin to lingerie rather than outerwear. Their length was felt to be ‘especially useful to for the busy young housewife and the younger girl who has not yet learnt to manage long skirts gracefully’.[56] In the later fifties nylon is increasingly used for housecoats. Wovenair Ltd specialised in quilted versions – which were promoted as providing ‘comfort while relaxing’. [57] The practical virtues of nylon are also emphasised: the ease with which it could be laundered – ‘wash, shake and dry on a hanger’; its crease resistance; as well as its light weight making it much easier to pack.[58] Although the longer housecoat continued to be seen, the formality seen in earlier examples had almost disappeared.

CONCLUSION

This paper has sought to explain the evolution of one specific garment, the housecoat, through the discourses developed by the trade press in order to promote its adoption by consumers. It has demonstrated that an examination of this largely neglected source material can shed light on how various elements of the industry talked to each other and grappled with the problems of developing a distinct identity for specific garment. The characteristic features of a housecoat were established in the late 1930s: full length; fitted bodice; capacious skirt; resemblance to an outdoor coat rather than indoor lingerie; along with its function as a suitable form of attire for informal dining. The confusions surrounding the housecoat’s meaning and function that emerged in the late 1940s and 1950s have their basis in the family of garments to which it was related. Consumers were expected to understand the appropriate time and location to wear each of the myriad of dishabille clothing that was available up to the end of the 1930s. In its efforts to secure new markets the industry attempted to simplify the products on offer to women, who may not have understood the nuances between garments such as the peignoir and the tea gown – their solution was the housecoat. Some claimed it was a brand new garment, but its semi-formal character expressed through tailoring, fit and fashionable styling demonstrates a direct link with the tea-gown, as does its function as a garment for semi-public display.

Once the housecoat was established in the early 1940s, there seems to be only a short period when there was a general consensus about its meaning and use. Suggestion of later confusion is hinted at during the war when there is an occasional mention of the garment’s multi-functionalism, this increases, until by the mid 1950s there is a bewildering array of explanations of the housecoat’s purpose, culminating in the garment being celebrated as ‘all-purpose’ and ‘comprehensive’. The trade’s inability to classify the garment clearly and to fix its meaning, reflected their failure to fully understand the changing lives of their potential customers. The reinvention and modernisation of an earlier garment was part of the problem. The contradictions that emerged in the trade’s explanations of the housecoat in the middle years of the twentieth century reflected society’s difficulty in categorising women – were they – ideal homemakers, glamorous hostesses, busy housekeepers or working wives – as they were variously described on the pages of Corsetry and Underwear? The response was to persuade the consumer that the housecoat was a perfect fit for every role a woman encountered – but this was not possible and the time had long passed when women would buy a different type of garment for each subtly different activity. It was not until the end of the 1950s, when the housecoat was recontextualised into a practical, loose-fitting, shorter garment worn over nightwear rather than underwear and the long, tight fitting, semi-formal version disappeared, that the trade was able to demonstrate that it had recognised the needs of consumers.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Ruth Addison; Andrew Clay; Katharine Short, De Montfort University Special Collections; London College of Fashion, Special Collections; Professor Lou Taylor; Ann Simpson; University of Nottingham Manuscripts & Special Collections

© The copyright for this piece rests with the author Christine Boydell. Every effort has been made to seek permission to reproduce the images included within this article – images and text from this article must not be copied or reproduced.

NOTES

[1] The term should not be confused with the garment worn by women to do domestic chores, confusingly also sometimes called a housecoat.

[2] Corsetry and Underwear (C&U) (sometimes known as Corsetry and Underwear Journal), formally Knitwear and Stockings was published by Circle Press in Leicester from 1935 to 1968, it became known as Foundationwear and Corsetry and Underwear and Bodylines from 1976. All issues were consulted at De Montfort University Special Collections.

[3] Whilst fashion and women’s magazines have received ample attention from academics, the trade journal is relatively neglected. The only substantial publication is Breward and Wilcox (eds) The Ambassador Magazine: promoting post-war British textiles and fashion (London: V&A Publications, 2012) which examines a specific magazine that promoted British exports.

[4] B.Hulanicki, From A to Biba (London: W.H.Allen, 1984), p.33.

[5] M.Swain, ‘Nightgown into dressing gown’, Costume, vol.6 (1982), pp.10-21.

[6] Woman in a Dressing Gown, (UK, J.Lee-Thompson, 1957)

[7] E. Post, Etiquette in Society, in Business, in Politics and at Home, (London: Cassell, 1969 [1922]) p.547.

[8] Good Housekeeping (May 36), p.63.

[9] Drapers’ Record (13.9.1930), p.484. Drapers’ Record was a journal established in 1887 to provide the clothing industry, particularly manufacturers and retailers, with news of relevant events in the political, financial, manufacturing and commercial world.

[10] ‘The housecoat is the newest version of the tea-gown’, Vogue (18 Oct 1933) p.87.

[11] Drapers’ Record (28 Aug 1937) p.134.

[12] ‘Autumn gowns are charged with formality’, C&U (July 1951), p.23.

[13] ‘The house-coat is here’, Drapers’ Record, (23 Dec 1937), p.50.

[14] ibid.

[15] C&U, (June 1939), p.29.

[16] Chilprufe catalogue 1938-9 (Uni of Nottingham Manuscripts& Special Collections – BCH/1/6/1/5)

[17] ‘The growth of housecoats’, C&U, (August 1945), p.22.

[18] C&U, (Oct 1941), p13.

[19] C&U (Aug 45) p.22.

[20] Pearl Binder was graphic artist and was married to Elwyn Jones who became a Labour MP in 1945 and later a life peer.

[21] Good Housekeeping, (August 1949), p.28.

[22] Draper’s Record, (2 Dec 1939), p.10.

[23] ‘Fashion in the home’, C&U, (July 1953), p.28.

[24] C&U (Sept 1944) p.21.

[25] C&U (Export Supplement 1949), p.VII.

[26] C&U (Oct 1941), p13.

[27] C&U (July 1946) p.11.

[28] Horrockses Fashions Limited. Extract from Verbatim Report of the Management Meeting, 29 November 1950 (LRO:DDVC Acc 7340 Box 12/3).

[29] ‘Taking shape’, C&U, (June 1953), p.47.

[30] Chilprufe advertising brochure ‘Presents of Chilprufe’ n.d. (Uni of Nottingham Manuscripts& Special Collections – (BCH 3.10.4.4).

[31] C&U, (Aug 1945), p.22.

[32] ‘Taking shape: housecoats hit the headlines’, C&U (June 1953), p.47.

[33] ibid

[34] C. Langhamer, ‘The meaning of home in postwar Britain’, Journal of Contemporary History, 40 (2005), pp. 341-362; J.Giles, The Parlour and the Suburb: Domestic Identities, Class Femininity and Modernity (Oxford and New York: Berg, 2004).

[35] C&U, (Feb 1942), p.12.

[36] Interview – Ruth Addison (May 2012)

[37] C&U (July 1955), p.32.

[38] C&U (July 1953), p.28.

[39] ‘For luxury lounging’, C&U, (July 1955), pp.32-41/

[40] Vogue, (Jan 1951) p.5.

[41] G. Robyns, ‘Are you a tatty viewer’, Evening News (18 July 1952) – (Lancashire Record’s Office: DDHs 49/2 1952-1955 Newscuttings Book)

[42] ‘Cool elegance: housecoat and fabrics for summer promotion’, C&U (Feb 1955), pp.44-53.

[43] Ibid., p.44.

[44] ibid., p45.

[45] ‘Fashion in the home’, C&U, (July 1952), p.28.

[46] ‘For luxury lounging’, C&U, (July 1955), p.32.

[47] C&U (June 1950), p.45.

[48] ‘Housecoats are high fashion’, C&U, (July 1959), pp.40-45.

[49] C&U (June 1950), p.45.

[50] ‘Winter elegance’, C&U, (July 1958), p.58.

[51] ibid., p.47.

[52] ‘Fashion in the home’, C&U, (July 1952), p.28.

[53] C&U, (July 1958), p.42.

[54] ‘The housecoat story’, C&U (Feb 59), p.42.

[55] In a feature from July 1959, ‘Housecoats are high fashion’ ‘shorties’ dominate with seven illustrated against four full-length. C&U, pp.40-45.

[56] C&U, (Feb 1957), p.54.

[57] C&U, (April 1957), p.73.

[58] ibid.

![Vam Tea gown, Worth, 1900 [Victoria & Albert Museum T.48-1961]](https://festivalofpattern.files.wordpress.com/2020/07/vam.jpg?w=328&resize=328%2C432&h=432#038;h=432)

![1942-44 MUM STANSFIELD BILLETTING US AIRMEN 1942-44 Pearl Binder billetting US airmen, drawn by Binder [Lou Taylor]](https://festivalofpattern.files.wordpress.com/2020/07/1942-44-mum-stansfield-billetting-us-airmen.jpg?w=323&resize=323%2C388&h=388#038;h=388)

![20160311_163827 A woollen housecoat, 1940s [Author's collection]](https://festivalofpattern.files.wordpress.com/2020/07/20160311_163827-e1594851698354.jpg?w=191&resize=191%2C388&h=388#038;h=388)

![New Image Horrockses Fashions, early 1950s [Author's Collection]](https://festivalofpattern.files.wordpress.com/2020/07/new-image.jpg?w=203&resize=203%2C323&h=323#038;h=323)

![20160311_161523 A late 1950s short housecoat [Author's collection]](https://festivalofpattern.files.wordpress.com/2020/07/20160311_161523.jpg?w=378&resize=378%2C677&h=677#038;h=677)

![10409885_10202794360232406_726173965_n[1] 'Campanile', no date](https://festivalofpattern.files.wordpress.com/2020/03/10409885_10202794360232406_726173965_n1.jpg?w=283&resize=283%2C472&h=472#038;h=472)